by Regina Smith and Maria Granville

New York State legalization advocates are rejoicing with the passing of MRTA (Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act). Finally, individuals, families, and communities most harmed by the war on drugs will get relief in the form of release from prison, automatic record expungement, and a halt to the non-stop harassment by police departments across the state that, in 2020 – twenty-one years after decriminalization – 57% of those arrested for marijuana-related arrests and summonses were Black. They are the MOST HARMED.

The price for this reform? Despite 40+ years of targeting and terrorizing Black communities, NYS just passed marijuana legislation that allows White medical cannabis companies (ROs) to monopolize recreational marijuana sales in NYS while Black entrepreneurs are blocked from building significant wealth in this billion-dollar industry.

Let’s start with the Medical Marijuana licenses. Enacted in 2014, NYS’s medical marijuana licensing program had no social equity component which explains why every RO is white owned. MRTA GUARANTEES that no social and economic equity licensee will ever be able to scale to the size of the current ROs that include Acreage Holdings (ACRHF), Columbia Care (CCHWF), Cresco (CRLBF), Curaleaf (CURLF), iAnthus (ITHUF), Etain Health (private), Green Thumb Industries (GTBIF), MedMen (MMNFF) (whose assets have mostly been sold to privately held Ascend Wellness), PharmaCann (private) and Vireo Health (VREOF).

Under MRTA, the existing ROs are the only companies that can have up to eight dispensaries with three of the eight coexisting with adult use. New entrants are limited to only three. The existing ROs are vertically integrated and are being allowed to increase production in each license category. New licensees can either be retail or wholesalers.

Vertical licensing is the most lucrative business model in the cannabis industry. Viridian Capital Advisors, who forecasts NYS marijuana sales will reach $1.9 billion by 2025, calculated that NYS ROs can achieve a 73% gross margin on the sale of one pound of flower while Social and Economic Equity retailers can expect 33%, and wholesale operators can expect to get 60%.

ROs also enjoy a tax advantage that social and economic equity licensees will not have. MRTA’s tax rate is 13% plus a THC tax. Medical marijuana is taxed at 7%, and companies like Green Thumb have already negotiated tax incentives that include a sales and use tax exemption and a 15-year property tax abatement with Orange county.

The very people who should benefit from the social and economic equity provisions will be paying a larger share of their income in taxes to support the 40% tax revenue targeted for communities most harmed than the current ROs who will dominate the industry.

The entire marijuana industry should be majority owned by those MOST HARMED, but not one state has developed legislation with that as the primary goal. New York is the only state to include Minorities, M/WBEs, women-owned businesses, disadvantaged farmers, and service-disabled veterans, who were not specifically or directly impacted by the war on drugs.

Black People fought for Affirmative Action and M/WBE initiatives but fail to benefit from them. In the 2015-16 school year, Black high school students constituted 16% of high school graduates nationwide, but they made up less than 5% of students enrolled at public selective colleges. White students comprised 52% of high school graduates, but they made up 63% of all students enrolled at state flagship schools the next fall. (Source)

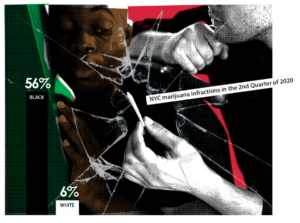

In FY 2020, White women and the Asian community together netted 84% of 1.97 billion dollars NYC spent with M/WBEs. Black businesses got 6%. Conversely, during the same time period, 56% of the individuals arrested for marijuana were Black while 3% were from the Asian community and 6% were white.

The state gave the NYS marijuana industry to the ten current medical marijuana license holders (ROs), and created a social equity program where the MOST HARMED will have to compete for licenses with individuals who have never seen the inside of a squad car.

Why do Black people and communities who have been harmed for 84 years have to compete with individuals who have not been or had a family member arrested, convicted, or incarcerated for minor marijuana offenses, or lived in a community terrorized by aggressive policing tactics that required every Black parent to have “The Talk”.

MRTA states the goal for Social Equity is to “make substantial investments in communities and people most impacted by marijuana criminalization to address the collateral consequences of such criminalization”. The pool of social and economic equity applicants should only include those who meet this criterion, no matter their race, gender, veteran status, or economic status.

The social equity provisions of MRTA does an excellent job in addressing social remedies, but the economic provisions seem designed specifically to benefit groups who have never seen, or know anyone who has seen, the inside of a police car. To meet MRTA’s goal to “end the racially disparate impact of existing cannabis laws”, New York must legislate and regulate business advantages for only the MOST HARMED equal to or surpassing that of the ROs.

These issues can be addressed in the regulations that are currently being contemplated, and the NYS Department of Health must issue at least ten additional medical marijuana licenses specifically for the MOST HARMED.

The Cannabis Control Board and the Office of Cannabis Management play a pivotal role in setting the rules for cannabis regulation in New York State. The leadership, and specifically the Chair of the Board and the Executive Director of the Office, have disproportionate influence in how these rules will either empower or marginalize the equity community.

Between them, these roles will lead to the appointment of key positions (including the Chief Equity Officer), draft and promulgate regulations, issue all licenses, and enforce all regulations. The importance of populating these roles with culturally competent and sensitive individuals who understand the economics of Black wealth attainment in the cannabis industry cannot be understated.

NYS legislators were concerned that the cost of vertical integration would hinder the MOST HARMED’s ability to enter the market because of the enormous expense. We are confident there are at least ten MOST HARMED entrepreneurs in New York State who could raise the capital to be competitive with the current ROs and they should be given every opportunity to try.

Black people were left out of the distillery business at the end of prohibition. The numbers game, that employed hundreds of thousands Black people, was taken over in 1980 to become the NY Lottery while calling the current entrepreneurs tax cheats and denying them a mechanism to become agents. Now, despite medical marijuana

legalization in 36 states and adult use in 16, there are no publicly traded Black owned cannabis companies in the in the world.

Marijuana legalization is the opportunity for Black people to build generational wealth by building businesses.

Not one of the Social Equity programs in the United States has succeeded in meeting their stated goals. The legislation must be revised to meet the goal of providing Economic Restorative Justice to only those MOST HARMED, and every opportunity should be taken to develop legislation and regulations that provides a them a business advantage.